Last Christmas was just a test run

I miss you, you stupid, fuzzy bastard. Every single day.

Last Christmas was just a test run

I miss you, you stupid, fuzzy bastard. Every single day.

The trailer for the Kevin Smith’s 2014 film Tusk is as ambiguous as the film itself. For two and a half minutes, it is impossible to tell if you are watching a trailer for a comedy movie, a shlock horror flick, or something somewhere in between – a loving, though no less mocking, send up of the horror genre of the sort which were the rage in the first half of the 2010s.

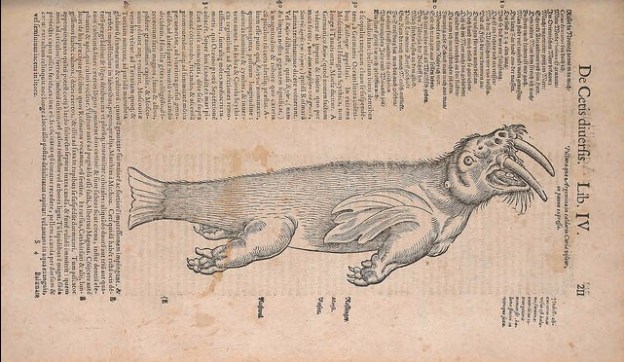

The basic set-up has a young, hot-shot podcaster going to Canada to interview a well-traveled old man, only to be drugged and abducted by his prospective interviewee who plans to transform him into a walrus. (That’s right.)

Obviously, the events of the film defy all logic – be it scientific, medical, or rhetorical – but they are executed with such unflinching dedication and apparent sincerity so as to demand the audience suspend their disbelief and meet the movie on its terms.

Justin Long is deeply hateable as Wallace Bryton, host of a successful humiliation comedy podcast with the puerile, though provocative, name: “The Not-See Party.” At the risk of attributing meaning where none was intended, Long’s performance may succeed thanks to the implicit moral law: only a complete asshole could find himself in such a situation.

Genesis Rodriguez plays Ally Leon, Bryton’s longtime girlfriend. Rodriguez is the true star and emotional core of this film, without her tender and engaging performance the movie would have devolved beyond its barely manageable absurdity into pure farce.

Haley Joel Osment carefully navigates the divided loyalties familiar to anyone with a best friend completely outclassed by their better half. Osment’s Teddy Craft struggles to balance his involvement with Wallace’s podcasting fame fueled antics and his recognition of increasingly unattractive qualities his friend has developed as a result of success. Osment manages the convoluted emotions demanded of his character with grace and a persuasive friendliness.

Meanwhile, Michael Parks and Johnny Depp (almost entirely unrecognizable under a terrible wig, false nose, and exaggerated not-quite-Quebecois accent) compete for the distinction of most bizarre and unsettling performance.

Parks projects an unsettling menace without ever appearing physically threatening. The psychosis he reveals with every wild-eyed pronouncement is a performance wasted on his would-be interviewer. Long’s Wallace is dedicatedly vacuous and self-involved, ensuring that each scene he shares with Parks incites a piteous horror of the sort usually reserved for small, stupid animals. Parks unflinchingly executes a performance which demands everything from waxing poetic about an animal otherwise banished to satiric 19th century poetry (familiar from another Kevin Smith film, Dogma) to deranged vocalizations and low brow caricature.

Depp’s Guy Lapointe is a washed-up Inspector Clouseau, beaten down by the world and haunted by his past failures, keeping all of the exaggerated ridiculousness of a Peter Sellers’ character and adding an incongruous sense of grief and world-weariness.

Were Depp’s character the beaten down, veteran gumshoe in any other film, he would certainly drink too much. Instead, Smith writes in the fast food diner equivalent of the raw egg hangover cure routine, leaving the desperate protagonists to lay their plight in the dubious – and, in this case, greasy – hands of the only man willing to take them on.

When Parks and Depp share the screen, scenes that would have, at best, been satires of stereotype, become distressingly unsettling and perverse, suffused with a menace that originates as much in the distorted portrayals as it does in the narrative context.

The special effects have that rubbery quality particular to practical effect, yet are no less unsettling or horrific for it. Give the propensity for gory realism and smooth CGI in so much of contemporary cinema, the return to silicone and painted foam exacerbates the conflicting impulses present throughout the film. They are patently ridiculous and heighten the un-reality of the mechanics of the plot, simultaneously, however, they have the inescapable materiality of something that exists.

Smith’s filmmaking is impeccable. He wields the misdirection of the frame and the editing suite to maximum effect, especially in the scenes which delve into the unexpectedly complex relationship ensnaring Wallace, Ally, and Teddy. The film establishes a pattern of flashbacks early on, lulling the audience into a sense of security. The slow unfolding of a dreamy, already unreachable, sun-dappled status quo illustrates the depths of Wallace’s douchebaggery, while demonstrating the genuine affection – rooted in what little remains of the young man she fell in love with – which ties Ally to this undeserving cretin.

Imagine the serial killer logic of Criminal Minds, the inventive and perverse body horror of The Human Centipede, and the wacky, irreverent – yet nonetheless emotional – hijinks of 90s slacker cinema, each taken to their logical extremity simultaneously.

You might then, for the briefest of moments, catch a glimpse of the feverish nightmare that is Tusk.

The commitment to seeing the film through without giving in to the nudge-nudge-wink-wink of irony is quite possibly the thing which makes it surpass all other recent horror films in terms of absolute perversity. It has none of the ironic trope inversions which made Tucker and Dale vs. Evil or Cabin in the Woods so delightful. Instead it operates with the white-knuckled sincerity of a horror film unselfconscious of genre.

Somehow, regardless of the way it should absolutely be a bad joke, Smith never breaks the tension, keeping the audience captive (quite possibly against their will and their better judgement) up until the very end. The audience is left dangling over the abyss, uncertain if the soft cushion of a punchline awaits them at the bottom. Without ever telegraphing whether the story will end on a laugh or a piteous cry, Kevin Smith has brought the metahorror of cognitive dissonance to its apotheosis. The film traps the audience in that moment where they are uncertain whether or not they should laugh.

After all, a joke without a punchline is a horror story.

“I KNOW IT HAPPENS TO EVERYBODY, BUT IT’D NEVER HAPPENED TO ME,” HE SAID. “I KNOW PEOPLE’S MOTHERS HAVE DIED, BUT THIS WAS MINE.”

OSCAR ISAAC, NEW YORK TIMES. 6 JULY 2017.

Isn’t that the process of growing up? Realizing that everything that has ever happened to you has happened before to someone else. What we need to remember, as adults, is that all children, as they grow up, are discovering life all for the first time. Their pain is bright and new and unlike anything they have ever felt before. We must remember that for all the repetition in the sum total of human experience, each individual encounters each of these forgone conclusions as a revelation, something awesome – in both its terror and its glory.

I ate dinner at home.

Before I left, a little while before, Blueberry had either found or killed (or, at the very least, maimed) a rather large beetle. Not quite a stag beetle – I don’t think we have those in this part of the country – but a 1.5 inch long, glossy black beetle.

She was curious about it and kept trying to eat it, but I got the impression that, legs up, it was too spiky or shocking for her to be able to fit it in her mouth.

She proceeded to scrabble at it, pushing the beetle’s invisible black body along the mess of flat stones which constitutes a walkway, along the edge of the deck, from the gate to the porch door, in that part of the garden.

She would pounce, sniff, taste, rear back, push— pounce, sniff, taste, rear back, push— again and again. Her white paws and startled reaction, the direction of her fixed gaze, the only things to give any indication of where her immobilized prey had ended up.

She must have scraped the body – head-thorax-abdomen – of that poor creature across ten inches or a foot, in a clatter of rough claws on slate, and the imagined rasp of carapace on stone.

Eventually, some significant damage must have been done. She leaned down, her blunt, curious snout pressing against stone and dirt, before lifting up her head.

Pitbull lips flapping, I could hear a sharp crunch-crunch-crunch. Satisfied, she trotted away in to the dark of the yard.

Retroactively published 22 Jan 2019

Two weeks ago (maybe more, maybe less) a friend and I sat down and started discussing philosophy.

I struggle to get along with optimists. Not to denigrate or dismiss them, because I think it’s beautiful to be able to believe in the best possible outcome. It is simply not something I am always able to entertain or understand. For me, optimism takes work.

The opposite of optimism is pessimism; the belief that everything will go wrong, all attempts will end in failure, and happy endings are impossible. This is the diametric opposition of the optimist, who believes that things will be okay, things will work out, and happy endings are always possible.

I am not a pessimist.

I consider myself a cynic. What does that mean exactly? It can’t be the same as pessimism, despite the fact that the words are often used interchangeably. Why does cynicism feel apt, where pessimism is grating?

The cynic, in my mind, is one who is ever hopeful, someone who dreams of happy endings, who wants things to work out. But. (And there is always a “but” with the cynic, it’s true.) Despite all that wanting, despite the dreaming, they’ve been frustrated too many times to believe that things will work out. The cynic reads the paper in the morning and weeps, because every morning they hope that the news will not be a litany of tragedies (though they know, every morning, when their feet touch the floor, that they should expect something terrible).

The cynic has taken a bad bet. Because the cynic will bet on the underdog, the new-comer, the good man knowing that they will lose. This is where the cynic and the pessimist differ; the pessimist has no desire to be surprised. The cynic is ever hopeful that this time, things will be different (despite knowing the odds).

So who is the opposite of the cynic? It is not the optimist, for they are static, just the same as the pessimist; they both look down the long uncertain road ahead, and see the light at the end, one sees sunlight, the other the on-coming train. The cynic is waiting, hoping for sunlight, and expecting the train. Who sits with them in that uncertainty?

My friend said, “Faith.” And she was correct.

Faith is that which sustains people in times of uncertainty. Faith is not optimism; it doesn’t promise that everything will work out for the best. Faith is an abiding belief in the future, that when the road is long and dark, something warm and safe awaits at the end of the road. Faith never promises a journey absent of strife, danger, and suffering. Faith promises that one can always take another step; look how far you’ve come.

The cynic and the faithful sit together in the dark, they know the odds. They know that the road is long and dark, and they both hope for the best. The difference is that the faithful knows the strength of hope. They know that hope is capable of sustaining someone, so long as you are a true believer.

The cynic, by contrast, is not quite strong enough. The cynic knows what hope tastes like, but doesn’t know how to make it grow, does not know how to harvest it, how to bake it into what they eat.

On days when I have to attempt great works, I sometimes wish I could have the strength of the faithful. There is a certainty to faith, to optimism, to pessimism that can seem enviable.

On every other day, I welcome the spark of doubt that lives within my cynicism. It is a balancing act, a middle path. The cynic can dream of heaven and keep their feet on the ground. One must be able to see clearly to know what is broken and one must have tasted hope to know what is possible.

Without cynicism, I would not be able to do the things I dream of doing. Cynicism is both that which arms to me examine how we have failed as a people, as a species, and where we have done wrong, it is the expectation of being beaten down, of being lied to, of finding victims and perpetrators. But it is also cynicism that makes me believe that we can do better, that we can improve, that we can apologize and heal.

I’m not sure I recommend it. The cynic is always expecting disappointment and, unlike the pessimist, they are not ready to accept it. But it’s a fighting spirit; still hoping for the best, despite their expectations.

Over the weekend, I visited the RISD Art Books Fair with a friend.

The first question is what is an “art book fair” – are they books about art? Is the library selling off old bits of its collection? Are they books that constitute art? None of the above?

The answer, as always, is complicated. Over all the event leaned into the notion of “books as art” with a healthy dose of “art fair” holding the whole thing together. Representatives from a variety of organizations of creatives were in attendance. Most of the stalls were RISD affiliated, showcasing the work of RISD students, past and present.

My friend and I spent a solid chunk of time pouring over the table half-covered with little, 2 cm in diameter buttons, each with a colorful background and a handwritten statement on the front. “No thank you” read one, “pseudonym” read another, “kind of a drag” read one that I bought, “solid blood” read one my friend bought. There was no method or reasoning to the text that we could discern, but nor did we care to look for one. It was time well spent swimming through the vague thoughts forms of the subconscious.

I picked up two little chapbooks by a graphic design student from the Kansas City Art Institute.

Selecting art books, like buying other kinds of art, is an exercise in self-discovery. It is never clear why you prefer one thing over another, why you want this work of art and not that one. Nevertheless, the feeling is always concrete, always strong. There is no rationalizing it, no secret formula to understanding it; art one brings home becomes a housemate, a companion. So it is also with art books. They call out to us, and we pick them up, and when we bring them home, we find ourselves sitting there, leafing through, curious, always trying to look with new eyes.

Knowing a piece of art can only happen with time. The thing which originally drew us to it is almost immediately papered over, hidden by every subsequent detail we find which pleases us. We put ourselves in dialogue with the piece by accident; simply by spending time with it, little details are revealed, “Oh, look at that little shape there” and “Oh, that shade of blue reminds me of the first house I remember us living in” and “Oh, how melancholy”. We are revealed as much as the art is revealed as much as the artist reveals. Indirect communication and accidental resonances take over.

Retroactively published 22 Jan 2019