There are many important things that have occupied my thoughts lately, but at the moment where I set fingers to keyboard to try and sort them out, they disappear.

I have an extreme backlog of reading (I shudder to think of how many browser tabs I currently have open) and plan to spend the day making my way through as many of them as I can.

I recall what I wanted to say:

Much talk has been bandied about lately about who needs to do which work, and what work needs to be done. What do we do with the legitimization of racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, Islamophobia, misogyny, cronyism, violence, and impotent rage? Who is responsible for this outcome? How do we make sure the impact is minimized and the people who now have targets on their backs get through this with as little damage as possible?

Many people feel that speaking to, listening to, engaging with the people who put us here––with this President elect preparing to take office––is not only to ask for something that is impossible, but that is actively destructive.

We don’t need to speak to these people, they say. These people want us dead.

The easiest example is the back and forth argument about whether being a Trump supporter makes you racist or not. I am inclined to believe that it makes you a racist, in that his language did not immediately mark him as an illegitimate candidate. I do not think it means that you want to degrade and subjugate the people he spoke against.

Such a distinction is trivial ultimately.

I do believe––strongly––that to denounce and vilify the quarter of the population who voted for Donald Trump would be a cataclysmic error.

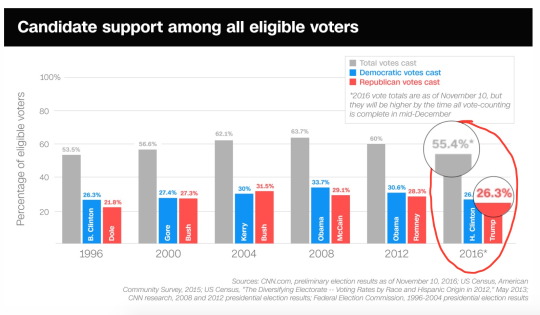

(graph from CNN, November 11.)

First, they are not necessarily a majority. They are a quarter of the population. One of our biggest concerns should be connecting with the other half the population, that did not feel it was necessary, important, or were unable to vote in this election. We need to determine what kept them from getting to the polls, and take action to remedy those inhibitors (be it voter suppression, political apathy, economic lack of access, whatever). If we believe that democracy and political freedom are important, we need to secure the rights necessary for those outcomes for the entire population, regardless of their political affiliation.

Second, we need to connect with that other half of the population and determine how many of them share our concerns about the direction of the country under Donald Trump. He may be determined to turn this country into a demagogic kleptocracy on par with Russia (taking the future of the planet with it; environmentally, politically, and economically), but, at the expense of sounding like the Right and far too many member of the GOP lately, we do still have the Constitution, and this is still a country founded on the principle: By the people, for the people.

Anyone who wants to point out that we have never lived up to that ideal is welcome to do so now. We still need to use every tool at our disposal. More importantly, we need to take action to make that ideal a reality. To borrow another slogan from the other side: freedom isn’t free. If we want a government for the people, by the people, we’re going to have to hold up our end of the bargain, and push for it. By the people.

Third, we need to bridge the gap––social, economic, political––between the coasts and the middle of the country. The political response and the rhetorical and ideological alignments that Trump supporters have chosen to express their grievances are hostile and reprehensible. That does not mean that all of their grievances are baseless or based in racial anxiety.

The social and economic dislocation that is occurring in the empty stretches of land between our borders is not all that different from the social and economic dislocation being experienced around the world as modernity and globalization fundamentally reshape and restructure our lives and livelihoods. This extremist wave is the backlash we saw once already when modernity and globalization first crept across the borders of Europe and the West, bringing to life fascism, futurism, nazism, and the first and second world wars. We are seeing it now on a larger scale in a more totalizing form.

That dislocation must be addressed. It cannot be allowed to progress unfettered, and it is not a specter conjured in the minds of people with something to lose. It is a reality of people who are already losing what they cannot afford to do without.

That does not mean that everyone must shoulder that burden equally. This is the moment where the white citizens of America, who have lived with privilege that far outweighs their right, must prove themselves patriots, and true allies and fellow soldiers in the war for equality and community.

We cannot allow the burden of speaking out against this hatred, and the work of building the bridges that will bring us, the majority, the disenfranchised, the precarious, together that we can aim our anger upward towards the targets deserving of it.

We cannot afford to atomize and balkanize. To fall into pieces will be a death sentence and leave us at the doors of annihilation. Our only hope is to succeed where all our ancestors have failed, and build the coalition which sees us as dependent on one another and responsible for each other.

We can only succeed together.